More Information

Submitted: December 05, 2025 | Accepted: December 12, 2025 | Published: December 15, 2025

Citation: Bliss EG, Srour H, Denny C, Damron JK, Lemoine NP. Progressive Maternal Heart Block in Pregnancy Requiring Transvenous Pacing: A Case Report. J Clin Intensive Care Med. 2025; 10(1): 031-034. Available from:

https://dx.doi.org/10.29328/journal.jcicm.1001055

DOI: 10.29328/journal.jcicm.1001055

Copyright license: © 2025 Bliss EG, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Progressive Maternal Heart Block in Pregnancy Requiring Transvenous Pacing: A Case Report

Emily G Bliss1* , Habib Srour2, Christopher Denny3, James K Damron4 and Neva P Lemoine4

, Habib Srour2, Christopher Denny3, James K Damron4 and Neva P Lemoine4

1University of Kentucky, Department of Anesthesiology, Perioperative, Critical Care, and Pain Medicine, Lexington, KY, USA

2University of Kentucky, Department of Anesthesiology, Perioperative, Critical Care, and Pain Medicine, University of Kentucky, Division of Critical Care, Lexington, KY, USA

3Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Department of Anesthesia, Division of Cardiac Anesthesia, Cincinnati, OH, USA

4University of Kentucky Department of Anesthesiology, Perioperative, Critical Care, and Pain Medicine, Division of Obstetrical Anesthesia, Lexington, KY, USA

*Corresponding author: Emily Bliss, University of Kentucky, Department of Anesthesiology, Perioperative, Critical Care, and Pain Medicine, Lexington, KY, USA, Email: [email protected]

Atrioventricular heart block (AVHB) encompasses a class of conduction abnormalities characterized by impaired electrical signal propagation within the heart. Based on the degree of dissociation, significant hemodynamic derangements may occur. During labor, rapid fluctuations in vagal tone and subsequent neurocardiogenic reflexes can cause further bradyarrhythmia and hemodynamic instability, requiring prompt intervention. This case describes a 21-year-old female with new-onset, progressive AVHB requiring transvenous pacing for labor induction and subsequent leadless pacemaker implantation post-delivery. Ultrasound-guided placement of temporary transvenous pacing wires offers a non-fluoroscopic option for management but necessitates ICU admission. This case highlights the need for novel standardized institutional protocols to ensure rapid ICU access for all obstetric patients requiring critical care. A structured approach to accessing critical care environments and interdisciplinary teams is necessary to reduce morbidity and mortality secondary to obstetric complications, including maternal AVHB.

Atrioventricular heart block (AVHB) encompasses a class of conduction abnormalities defined by impaired electrical signal propagation within the heart. Based on the location and degree of dissociation, significant hemodynamic derangements may occur. These derangements are exacerbated during the active phase of labor secondary to rapid alterations in vagal tone, resulting in neurocardiogenic reflexes with further bradyarrhythmias and hemodynamic instability [1,2].

Although data on new-onset AVHB in pregnancy are limited, common causes in healthy young adults include undiagnosed congenital conduction abnormalities, medications, autoimmune disorders, infiltrative diseases, and various infectious processes [3,4]. The incidence of congenital AVHB is estimated to be 1 in 15-20,000 live births and often remains asymptomatic into adulthood [5,6]. However, the incidence of new-onset AVHB in pregnancy is unknown. While AVHB in pregnancy is often asymptomatic, the fetus is at increased risk for congenital cardiac abnormalities in the presence of circulating autoantibodies [7].

This care report emphasizes the importance of prompt recognition of maternal AVHB in pregnancy and active anticipation of neurocardiogenic reflexes during the active phase of labor. The use of temporary transvenous pacing wires placed via central access under ultrasound guidance is a safe, non-fluoroscopic management option; however, it necessitates ICU admission. This case highlights the need for novel standardized institutional protocols to ensure rapid ICU access for all obstetric patients requiring critical care.

A 21-year-old G2P1001 at 39 weeks and 3 days gestation presented for an elective induction of labor. Medical history included well-controlled asthma, mild scoliosis diagnosed in childhood, and a remote history of osteomyelitis requiring intravenous antibiotics. This pregnancy was complicated by a new diagnosis of asymptomatic AVHB of non-specific degree. On admission, her vital signs were stable with an asymptomatic resting heart rate of 55 beats per minute.

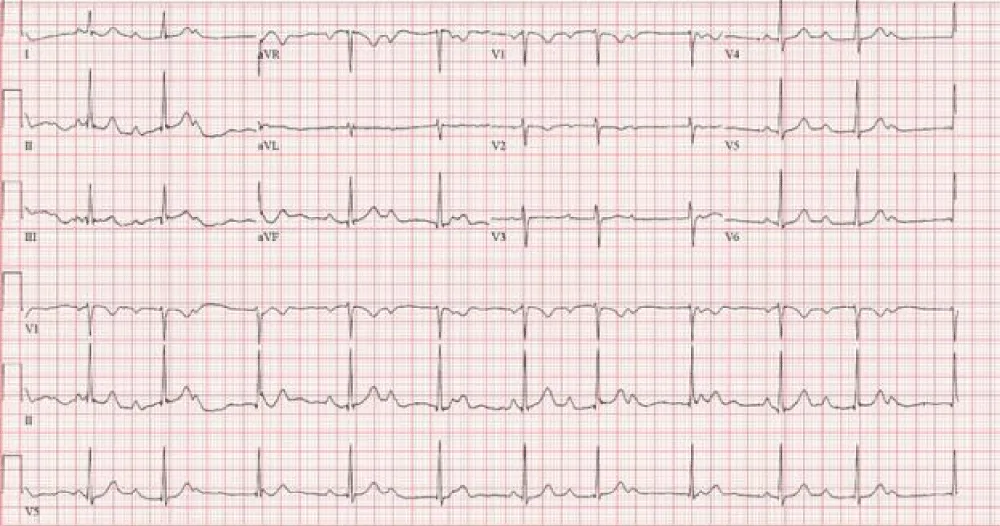

Six months prior, the patient presented to the emergency department with a 2-day history of sore throat, chest pain, abdominal pain, and dizziness. Electrocardiogram (ECG) demonstrated a new second-degree AV block (Mobitz I) (Figure 1). Trans-thoracic echocardiography (TTE) revealed no structural abnormalities. Laboratory tests, including an infectious workup, were unremarkable. Following an extensive history and medication review, cardiology attributed the AVHB to increased vagal tone in the setting of an acute cough and pain, with low suspicion for progression. The patient was discharged home with a 7-day ambulatory ECG device and outpatient cardiology follow-up.

Figure 1: ECG from the emergency department showing sinus rhythm with 2nd degree AV block (Mobitz I) at a rate of 66bpm.

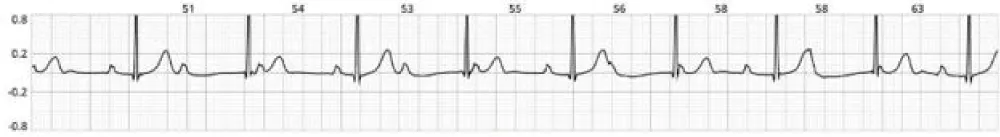

On follow-up, the ambulatory monitoring revealed an underlying first-degree AV block 81% of the time with intermittent episodes of third-degree AV block during sleeping hours (Figure 2). One daytime episode was recorded while the patient was napping. Cardiology recommended a sleep study to evaluate for the presence of sleep apnea and repeat ambulatory monitoring in the post-partum period. No changes were made to the delivery plan.

Figure 2: Rhythm strip from ambulatory monitoring showing an episode of 3rd degree AV block at a rate of 55bpm.

Two months later, the patient presented to the obstetric triage following a syncopal episode. She described sudden-onset dizziness while getting dressed, followed by a witnessed loss of consciousness lasting a few minutes. Vital signs were stable, and the neurologic exam was unremarkable on arrival. Laboratory tests, including electrolytes, were unremarkable. ECG again revealed first-degree AV block. Cardiology recommended admission for further monitoring; however, the patient declined due to symptom resolution.

Labor and management

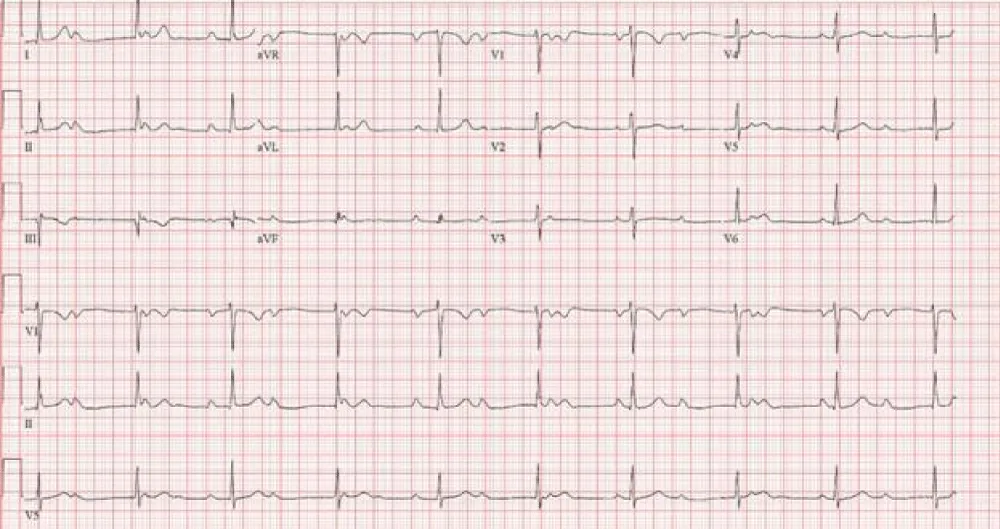

On admission for induction of labor, the patient reported no recurrent syncopal events or symptomatic bradycardia. An ECG was obtained, which revealed complete AVHB with a narrow junctional escape rhythm at 56 beats/minute (Figure 3). Laboratory tests, including electrolytes, were unremarkable. Cardiology noted that the narrow junctional escape rhythm suggested the patient might tolerate labor without cardiac complications and advised against prophylactic placement of temporary transvenous pacing wires due to fetal radiation exposure. Further recommendations included advanced cardiac life support (ACLS) algorithms, transcutaneous pacing with sedation, and isoproterenol for chemical pacing should significant bradycardia resulting in hemodynamic instability occur.

Figure 3: ECG from obstetric triage showing sinus rhythm with complete heart block with junctional escape rhythm at 56bpm.

After further discussion with the patient, who strongly preferred a vaginal delivery unless in the event of an emergency, it was agreed upon to proceed with early placement of a labor epidural. A multidisciplinary team, including high-risk obstetricians, cardiology, electrophysiology, and obstetric anesthesiology, determined that the patient warranted intensive monitoring and would benefit from placement of temporary transvenous pacing wires given her high risk for vagally-mediated bradycardia and hemodynamic instability during labor. Therefore, the patient was admitted to the cardiac ICU under the anesthesiology critical care team. Transcutaneous pacing pads were placed on the patient as a precaution, and ACLS medications were made available. Due to institutional restrictions, isoproterenol was unavailable outside of an intensive care setting.

In the ICU, temporary transvenous pacing wires were successfully placed via the right internal jugular vein by obstetric and critical care anesthesiology teams under ultrasound guidance. Overnight, telemetry confirmed intermittent complete heart block with a ventricular rate of 30 beats/minute requiring pacing. Fetal heart rate tracings remained reassuring during these episodes.

Labor induction was initiated the next morning. A lumbar epidural was placed without complications, and labor analgesia was initiated slowly and maintained using a patient-controlled infusion of fentanyl (2 mcg/mL) and bupivacaine (1 mg/mL). Hemodynamics remained stable with a bilateral T9 sensory block.

Labor progressed with amniotomy and oxytocin augmentation. Throughout labor, the patient required intermittent ventricular pacing due to complete AVHB with a ventricular rate of 30 beats/minute. Before the second stage of labor, ACLS and emergency medications, including isoproterenol, were made available at the bedside, and pacing wire functionality was repeatedly verified. She successfully delivered a healthy male infant later that evening. The delivery was complicated by a 20-second shoulder dystocia without resulting neurologic damage. Outside of bradycardia requiring pacing, no additional significant cardiac events occurred. The epidural was removed following delivery.

Outcome

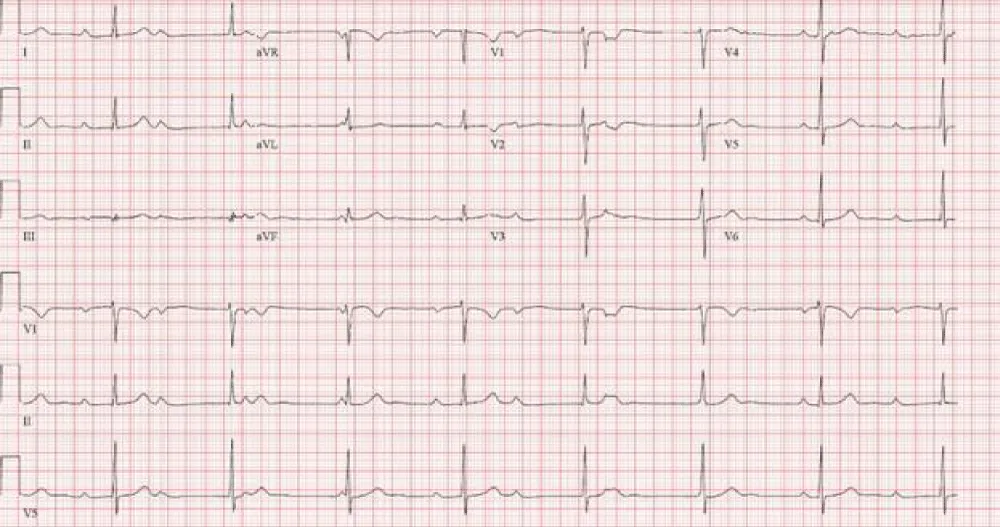

Postpartum, telemetry revealed persistent complete AVHB requiring ventricular pacing both while awake and sleeping (Figure 4). Following re-evaluation by cardiology and extensive discussion with the patient, the decision was made to proceed with the insertion of a permanent leadless pacemaker. Three days postpartum, the pacemaker was placed in the cardiac catheterization lab under local anesthesia without complication. Following pacemaker placement, the patient did not have any additional episodes of significant bradycardia on telemetry. She was discharged home along with her son the following morning in stable condition.

Figure 4: ECG showing underlying sinus rhythm with complete heart block and junctional rhythm at a rate of 47bpm before insertion of a permanent pacemaker.

Additional diagnostic evaluation for underlying etiology, including Lyme serology, Treponema pallidum, Covid-19, HIV, thyroid panel, and autoimmune titers, was unremarkable. On a two-week telephone follow-up, the patient reported that she was doing well. Her new son was also reported to be healthy, with no evidence of congenital conduction abnormalities.

Atrioventricular heart block (AVHB) encompasses a class of conduction abnormalities defined by impaired electrical signal propagation within the heart. Based on the location and degree of dissociation, significant hemodynamic derangements may occur. In pregnancy, heart block affecting maternal cardiac output can significantly impair uteroplacental perfusion, thus impacting fetal oxygenation. During active labor, rapid fluctuations in vagal tone and subsequent neurocardiogenic reflexes can cause further bradyarrhythmia and additional reduction in maternal cardiac output, leading to compromised uteroplacental perfusion [1,2].

Although data on new-onset AVHB in pregnancy are limited, common causes in healthy young adults include undiagnosed congenital conduction abnormalities, medications, autoimmune disorders, infiltrative diseases such as sarcoidosis or amyloidosis, and various infectious processes such as COVID-19, Lyme disease, syphilis, myocarditis, rheumatic fever, and Chagas disease [3,4]. Cardiovascular adaptations during pregnancy, including physiologic eccentric hypertrophy in response to increased circulating plasma volume and cardiac output, may contribute to new arrhythmogenesis [4]. While estrogen is historically thought to be cardio-protective through the inhibition of pathologic hypertrophy, there is evidence to suggest estrogen may alter gene expression, such as reducing levels of Kv4.3 and Kv1.5, resulting in altered ion channels and transporters leading to an increased susceptibility to various arrhythmias [8].

Placement of temporary transvenous pacing wires can be lifesaving in the setting of hemodynamically significant bradyarrhythmias. Methods for placement include ultrasound or fluoroscopic-guided. While fluoroscopy is considered the gold standard, there is evidence to support that ultrasound-guided placement reduces time to access, number of attempts, and overall radiation exposure, ultimately providing a safer alternative for placement of temporary transvenous pacing wires in pregnancy [9]. Due to the invasive nature of the procedure, risk of initial hemodynamic instability, and need for constant monitoring, ICU admission is required before placement. At the University of Kentucky, access to isoproterenol and other cardiac agents is restricted to ICU settings. In this case, the obstetric anesthesia team was able to directly consult and admit under the anesthesiology critical care team. However, institutional protocols protecting and further establishing this access do not exist. Aside from cardiac pathologies, one retrospective record analysis of all obstetric admissions in the ICU over 18 months revealed additional causes for admission to include hemorrhage, hypertensive disorders, uterine rupture, ectopic pregnancy, sepsis, peripartum cardiomyopathy, restrictive lung disease, and more [10]. Proposed protocols may include standardization of direct admission to ICU teams, access to fetal monitoring, uterotonic agents, and local anesthetics not commonly available in the ICU, access to NICU and fetal resuscitation supplies, and mitigation of physical distance between ICU and obstetric floors.

This case report emphasizes the importance of early recognition, multidisciplinary planning, and anticipatory management of obstetric patients presenting with progressive maternal AVHB. Specifically, during active labor, when rapid fluctuations in vagal tone in the setting of AVHB can result in significant hemodynamic instability and compromise uteroplacental perfusion. ICU admission for ultrasound-guided placement of temporary transvenous pacing wires via central venous access before the induction of labor offers a non-fluoroscopic option for managing maternal AVHB. This case further advocates for standardized institutional protocols ensuring rapid access to the ICU for obstetric patients requiring critical care. A structured approach to accessing critical care environments and interdisciplinary teams is necessary to reduce morbidity and mortality secondary to obstetric complications, including maternal AVHB.

Information within originates from within the United States and is prepared in accordance with the requirements of HIPAA privacy regulations. Written informed consent for publication has been obtained from the patient.

- Christensen A, Singh V, England A, Khiani R, Herrey A: Management and complications of complete heart block in pregnancy. Obstetric Medicine. 2021, 16:120-122. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1177/1753495x211033489

- Suri V, Keepanasseril A, Aggarwal N, Vijayvergiya R, Chopra S, Rohilla M: Maternal complete heart block in pregnancy: Analysis of four cases and review of management. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research. 2009, 35:434-437. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1447-0756.2008.00961.x

- Barra Snc, Providência R, Paiva L, Nascimento J, Marques Al: A Review on Advanced Atrioventricular Block in Young or Middle-Aged Adults. Pacing and Clinical Electrophysiology. 2012, 35:1395-1405. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-8159.2012.03489.x

- Collins HE: Maternal Cardiovascular Research and Education Should be Prioritized in the US. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2025, 328:Available from: https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpheart.00751.2024

- Baghel K, Mohsin Z, Singh S, Kumar S, Ozair M: The Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology of India. 2016, 66:623-625. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13224-016-0905-z

- Reid JM, Coleman EN, Doig W. Heart. 1982, 48:236-239. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1136/hrt.48.3.236

- Baruteau AE, Pass RH, Thambo JB, et al.: Congenital and childhood atrioventricular blocks: pathophysiology and contemporary management. European Journal of Pediatrics. 2016, 175:1235-1248. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-016-2748-0

- Murphy E: Circulation Research. 2011, 109:687-696. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1161/circresaha.110.236687

- Vitali F, Zuin M, Charles P, et al.: Ultrasound-guided versus Fluoro-guided Axillary Venous Access for Cardiac Implantable Electronic Devices: A Patient-Based Meta-analysis. EP Europace. . 2024, 29:Available from: https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/euae274

- Gupta H, Gandotra N, Mahajan R.: Profile of Obstetric Patients in Intensive Care Unit: A Retrospective Study from a Tertiary Care Center in North India. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2021, 25:388-391. Available from: https://doi.org/10.5005/jp-journals-10071-23775